Here’s how this graduated income tax proposal would affect Colorado residents’ take-home pay

The measure that seeks to eliminate Colorado’s flat rate in favor of a graduated income tax contains a dozen brackets, with the highest levels set to accrue tens of thousands more in liabilities, while cutting them for individuals at the lower ends of the proposed spectrum. How it would impact individuals will depend on their […]

The measure that seeks to eliminate Colorado’s flat rate in favor of a graduated income tax contains a dozen brackets, with the highest levels set to accrue tens of thousands more in liabilities, while cutting them for individuals at the lower ends of the proposed spectrum.

How it would impact individuals will depend on their annual household — or business — income. At the lower end, people could see their taxes cut by a few hundred dollars. At the highest end, individuals could pay hundreds of thousands more each year.

The proposal, a constitutional amendment, comes from a coalition of nearly three dozen progressive-leaning organizations led by the Bell Policy Center.

Broadly speaking, under a graduated income tax — which is also known as “progressive” tax — the rates are divided into brackets. The lower brackets pay a smaller rate; the higher levels are taxed a bigger rate. A graduated system would eliminate Colorado’s flat tax rate.

Currently, income is taxed at a flat tax rate of 4.41%. Everyone pays the same rate, regardless of income.

The measure’s proponents argue that higher income earners should pay more in taxes, while those at the lower end should get a tax cut. Critics said it would would hurt, not help, the state.

Those arguments are familiar in the long-running debate that perennially occurs across America over how to tax income. Supporters have long insisted that bringing in more tax revenue would pay for the state’s priorities, arguing programs are underfunded. Critics have countered that a graduated tax system that exponentially increases liabilities for some not only dissuades companies from moving to Colorado, it perpetuates the state’s problem of overspending.

The money generated by the ballot measure, should voters approve it next year, would bring in about $2.3 billion annually. As proposed, the money would primarily go toward K-12 and higher education, childcare, homeless or workplace initiatives, and health care programs.

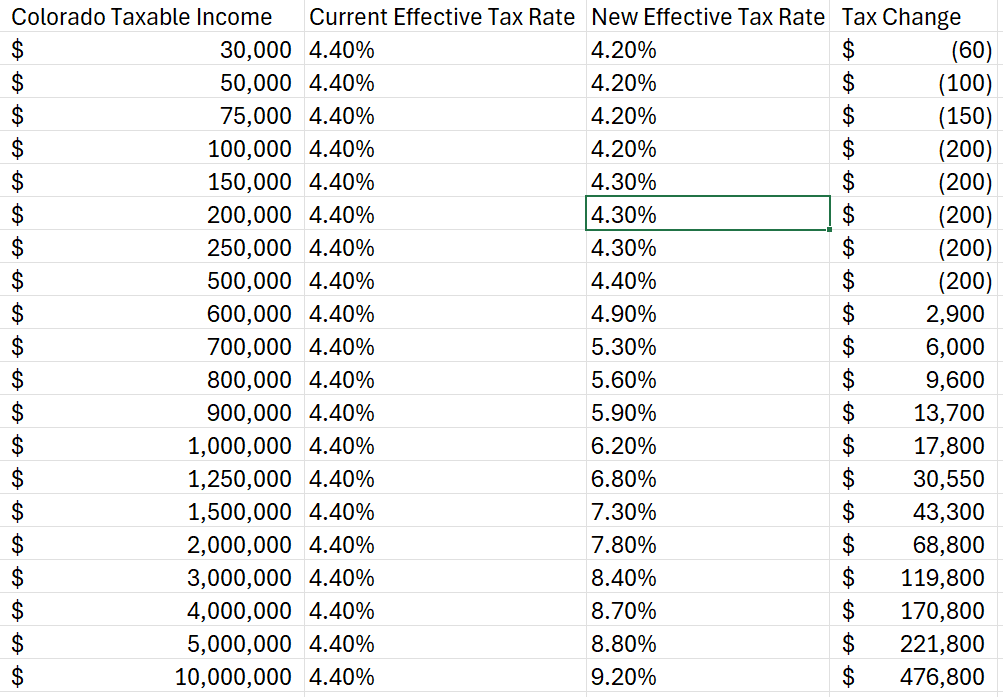

The chart below shows the different tax rates depending on income, and how much people might save or pay more in taxes; the ballot initiatives themselves explain the numbers.

Here’s what it would look like.

For incomes of less than $100,000, the tax rate would be 4.21%.

For incomes between $100,000 and $500,000, the tax rate is 4.21% for the first $100,000 and 4.41% for everything above that income. This applies to individuals, estates and trusts.

For incomes above $500,000 but less than $750,000, the tax rate is 4.21% on the first $100,000, 4.41% between $100,000 and $500,000, and 7.51% for income between $500,00 and $750,000.

Above $750,000 but less than $1 million, the tax rate starts the same — at 4.21% for the first $100,000, 4.41% for income up to $500,000, and 7.51% above $500,000 but less than $750,000, and 8.51% above $750,000 to $1 million.

For incomes above $1 million, the ballot proposal sets the same rates (see above) up to $1 million.

Above $1 million, the tax rate is 9.51%.

So, what does that mean?

If a resident’s income is $30,000 per year, that person currently pays a tax rate of 4.41% or about $1,323.

Under the ballot proposal, the rate would drop to 4.21%, or about $1,263, translating to a savings of $60.

The tax cuts get larger with a bigger income — up to $500,000.

At $150,000, for example, the state tax bill is about $6,615 currently.

Under the proposal, the first $100,000 would be taxed at 4.21% and the rest at 4.41%. That translates to a liability of $6,415, a savings of about $200.

Then the rates begin to increase above $100,000 up to $500,000, even though it still means a tax cut.

For a household with $250,000 in annual income, the current tax bill would be about $11,025. Under the proposal, it would drop to $10,825.00 — about $200 less.

At $500,000, taxes owed would be about $22,050 today. Under the proposal, it would be $21,850.00 — again, $200 less.

Above $500,000, it gets more complicated.

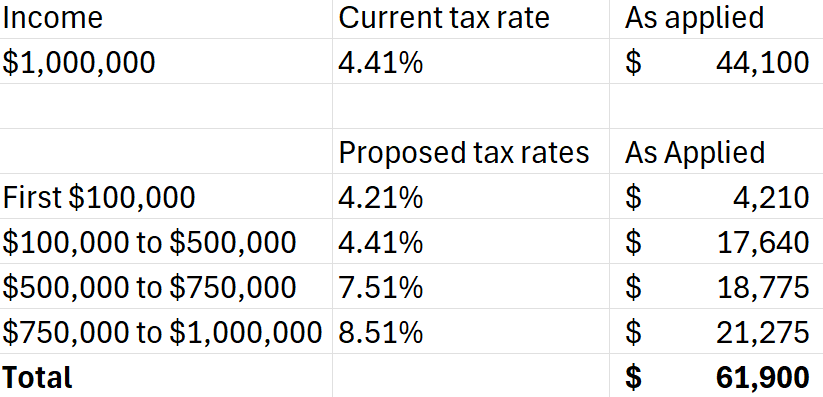

A household with a $1 million income currently pays $44,100.00. Under the proposal, the first $100,000 would be taxed at 4.21%; the next $400,000 would be taxed at 4.41%; between $500,000 and $750,000, the rate is 7.51%, and between $750,000 and $1 million, it is 8.51%.

The chart below shows how the proposed changes would affect that income:

That translates to a tax hike of $17,800.

Corporate tax rates would also change, affecting C and S corporations, according to the ballot measure.

An S corporation passes corporate income, losses, deductions, and credits through to their shareholders for federal tax purposes.

In a C corporation, the owners or shareholders are taxed separately from the corporation itself.

The tax rates are the same for the corporations’ net income as is spelled out for the individual tax rates.

So, who pays what?

Citing 2020 statistics of income data, the Bell Policy Center outlined the number of people in each category:

2,609,657 tax filers earned income below $500,000 annually. Of that group, 2,029,737 make less than $100,000 per year.

There are 26,360 tax filers with incomes above $500,000.

Of these: 8,448 make $500,000 to $750,000 and 6,336 earn between $750,000 to $1 million.

Finally, 11,576 Coloradans make more than $1,000,000 per year.